Understanding Engineering Momentum

The physics behind why platform adoption is harder than it looks

One of the mantras we repeat when building a platform is that we must treat it as a product. In practice, what we really mean is that we must put developers at the center of everything. But as you go deeper into the platform journey, you start realizing something important — a platform is not a normal product.

It doesn’t simply “fill a gap” the engineering team has, like a CI/CD system or an observability tool. A platform appears as a response to the dysfunctions of the engineering organization itself. A tiny startup with three engineers and zero process doesn’t need a platform. The need emerges later, when complexity starts multiplying and the company can’t move fast anymore.

Platform engineering looks great on paper. But in real life? It’s messy.

When you start in your platform journey, you will probably inherit systems, processes, cultural habits, expectations, deadlines, fires to put out. Everything is already in motion. And anything that tries to change that motion will face resistance.

I call this Engineering Momentum.

Understanding Momentum

In physics, momentum (“quantity of motion”) is the product of mass and velocity:

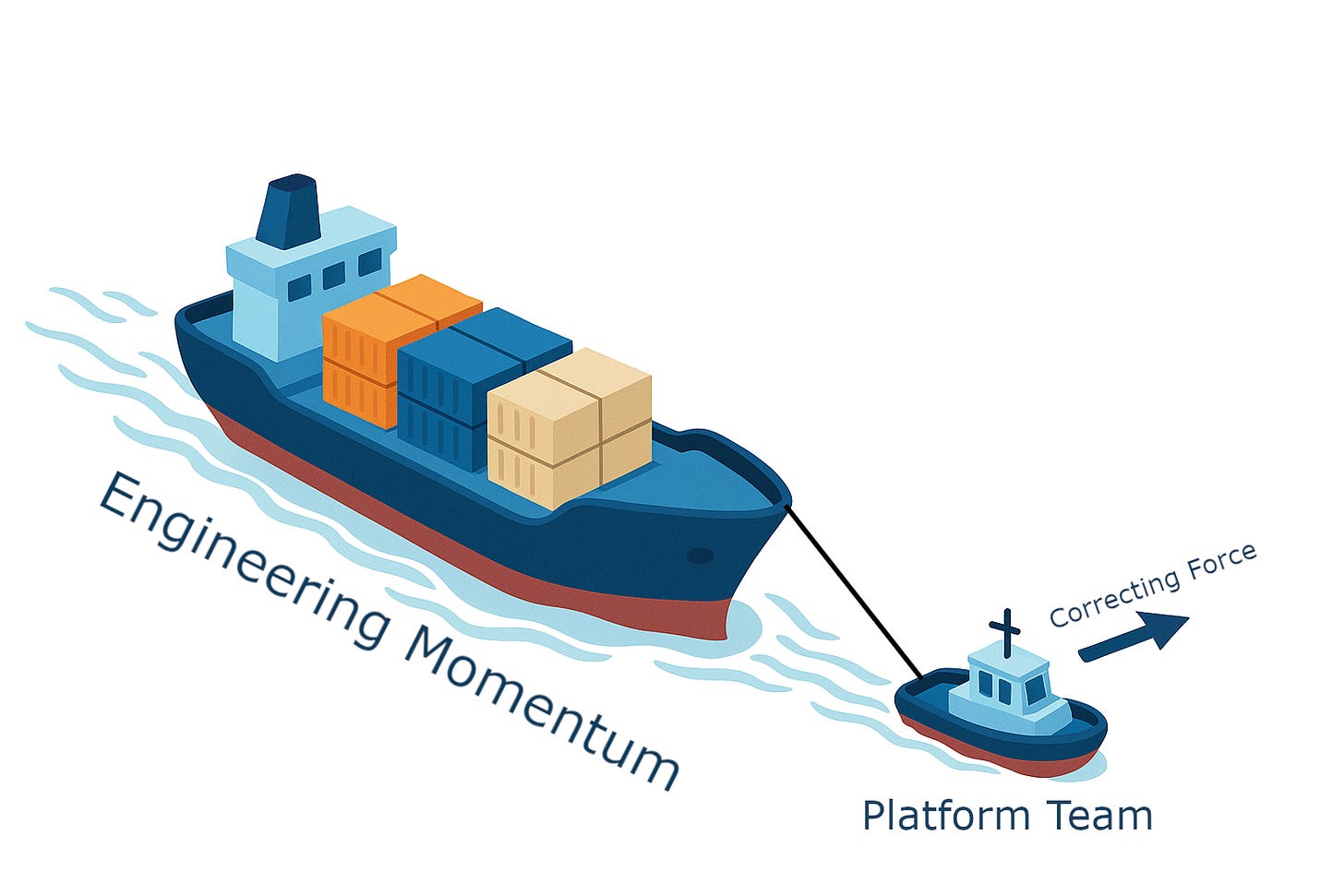

A fully loaded cargo ship traveling at cruising speed has enormous momentum, because of its huge mass. You can’t simply turn the wheel and expect the vessel to pivot sharply. It will fight you. It wants to keep going straight. To change its direction, you need to apply a gentle, continuous force over a long arc —sometimes with the help of a tugboat— to slowly bend its trajectory. There is no such thing as a sudden 90-degree turn in a ship that size.

Engineering is exactly the same.

Teams have mass:

people

habits

inherited processes

legacy tools

technology they’ve accumulated

interdependencies

historical decisions (that no one fully remembers)

And they also have velocity:

roadmaps

deadlines

commitments already made

business pressure

operational load

The bigger the mass and the faster the velocity, the greater the momentum. And the harder it is to change direction.

This isn’t just a cute analogy. It’s physics!. It’s exactly what happens in any technological transformation. And somehow, nobody talks about it explicitly.

Ignore Momentum and You Will Fail

This is, in my opinion, where many platform teams — and many internal improvement initiatives — crash.

There’s this assumption that “if the platform is great, people will naturally adopt it.” But that ignores the thing that dominates everything: engineering momentum.

You don’t walk into an organization, disappear for a year to build “the perfect platform,” and then return saying: “You can migrate now.” Because what you’ll find when you arrive is:

legacy systems

tangled processes

delivery pressure

competing priorities

habits cemented over years

And ironically, those are the very reasons the platform needs to exist. You want to simplify, standardize, reduce friction. But you cannot design a platform while pretending the real-world mess doesn’t exist and believing it will magically vanish once everyone migrates.

A platform introduces friction — even when perfectly designed.

No matter how good the platform is, if adopting it demands extra effort during a period of high load, teams will resist.

Sometimes consciously. Sometimes culturally. Sometimes without even noticing.

That’s momentum.

The Correcting Force

I’ve faced this several times, and in retrospective, it’s one of the most fascinating aspects of platform engineering. Sometimes it’s even more rewarding than the technical challenge.

Because a platform changes how teams work. It introduces new workflows, new tools, new rules. And that affects team velocity, mental energy, and psychological safety. It’s no surprise that change fatigue is such a common phenomenon.

This is why disappearing to build the “ideal platform” is a terrible idea. If a month goes by and you’re not helping solve real problems, someone will ask why the company is paying for a platform team. And they won’t be wrong.

A platform must be born with the organization, not in spite of it.

So before preaching “best practices” or pushing migrations, you need to start with something more humble:

Help with real problems. Even when they are not “platform problems.”

Earn credibility. Build trust. Reduce friction. Once teams see you solving issues that actually hurt them, they’ll be much more open to follow your lead.

And that’s when you can apply the “gentle, constant force” that slowly changes direction:

guidance

empathy

clear documentation

examples

golden paths

human support

collaboration

small wins

Little by little, momentum bends. The change stops feeling like an imposition and starts feeling like an obvious improvement. Because you’re no longer seen as “the team pushing a new thing,” but the team that helps to reduce the burden.

When that happens, adoption stops being a fight, and you can start introducing new technologies in the stack, new processes, and new culture for building software. Yes, that awesome Kubernetes and Argo CD to fully automate deployments that you want to put in place will come months later in the process.

Conclusion

Listen more than you impose.

Respect the team’s load before asking for effort.

Show value before asking for commitment.

Platform teams are not engineering police. We are strategic partners.

And when trust, consistency, and collaboration compound, something clicks. The engineering momentum stops pushing against you and starts pushing with you.

When that happens, everything flows.

Thanks for reading!